In hopes of “building a culture of peace from an early age,” Mexico City officials have included a component for children in the capital’s gun buyback program: exchanging toy guns for more educational playthings.

The little ones in the crowd couldn’t have cared less about the statistics: over 6,000 pistols, long guns, and even grenades recovered so far in the program. Over a million rounds of ammunition. Intentional homicides down over 60%. The kids didn’t come to “nurture peace,” as Mexico City’s Government Secretary Martí Batres expounded in front of the small crowd gathered in the churchyard — they came for the toys.

Many looked bored. A couple aimed their toy guns at their friends, siblings, and cousins who came to exchange them for the dinosaurs, puzzles, and soccer balls piled high on a table next to the stage. Plastic trigger clicks punctuated the speeches of the presenters.

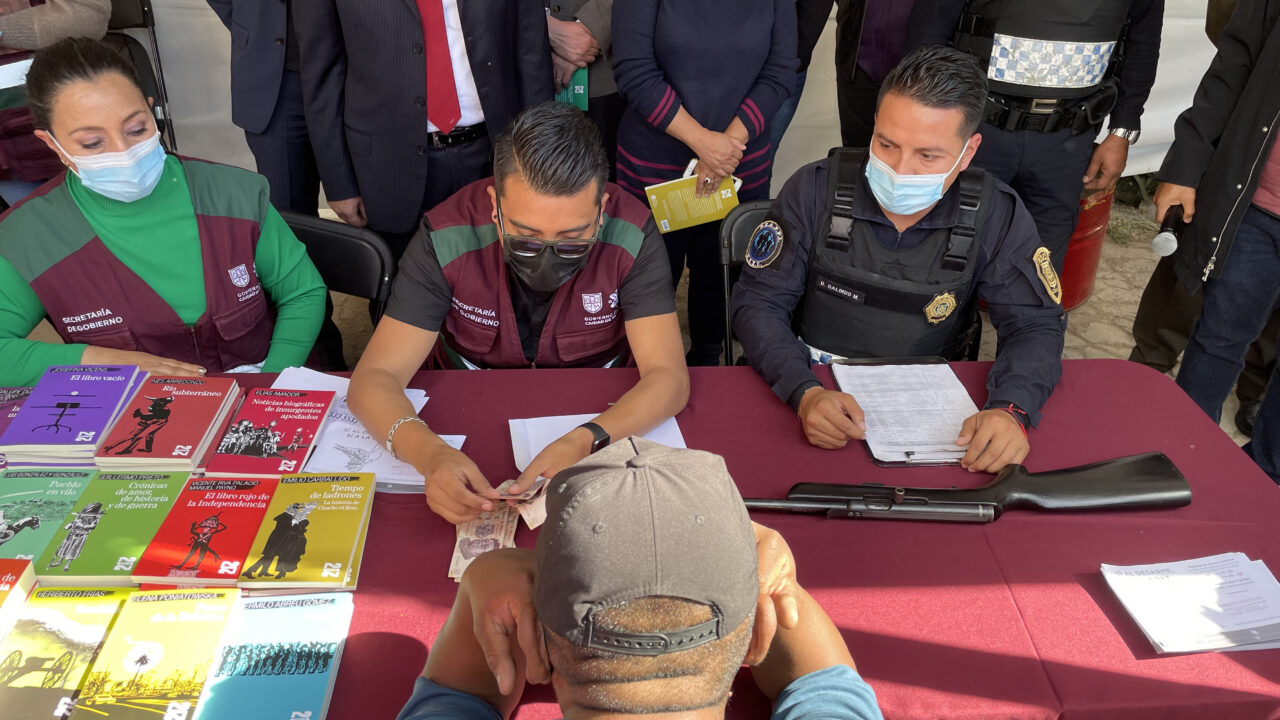

The kids and their parents came to the Saint Apollonia Parish in Mexico City’s Azcapotzalco neighborhood on Friday to inaugurate a new exchange center for the city’s gun buyback program called “Sí al Desarme, Sí a La Paz” (Yes to Disarmament, Yes to Peace). Officials say the program has contributed to the declining homicide and other crime rates in the city since it began exchanging arms for cash in January 2019.

While the program cannot take all of the credit for the cited drops in violence in Mexico City over the past couple years, Batres said that it “offers its grain of sand to reducing the rate of homicides in the home.” The city has also seen reductions in the numbers of injuries resulting from crimes, as well as assaults on public transportation.

In hopes of someday rendering the program unnecessary, the city government partnered with the National System for Integral Family Development (DIF) to offer something for the kids, as well. While soldiers and police officers wait to anonymously buy back real guns from citizens, DIF representatives will be on site to exchange toy guns and other toys that inspire violent play for didactic ones, such as puzzles, board games, sports equipment and more.

“Exchanging toy guns for educational ones is more than just changing out a violent toy, it’s a change in the culture,” said Nashelly Contreras Orozco, who heads up the Mexico City DIF’s Services to Girls, Boys, and Adolescents. “It creates an awareness in the children not to ask for toy guns and parents to not give toys that generate violent play.”

Parents were happy to see their children excited for the new toys they received. Brenda De Los Santos, a mother of three, said she believed in the program’s ability to change negative behaviors in her children. “It’s good, because it can help with the kids’ aggression,” she said.

Father-to-be Daniel Álvarez brought a gaggle of nieces and nephews to trade out the pieces in their plastic armory for toy dinosaurs, robotics sets, and a tower of Jenga blocks. “It gives the kids another way to play besides fighting, and they don’t create those habits of violent play,” he said. “They’re excited for their new toys. You can see it on their faces.”

So far, the program has exchanged over 9,300 toys. Contreras contends that domestic violence rates in the city have lowered as a result of the program, but it may be a little too soon to sing such praises. While intentional homicides may be down, statistics compiled by the National Citizen’s Observatory, a nonprofit that monitors conditions of security, justice and legality in Mexico, show the rate of domestic violence in Mexico City has been on a slight and steady rise throughout the life of the program.

The stats, however, do not serve to discredit either the gun buyback or toy exchange programs. Dr. Dinur Blum, a sociologist at California State University, Los Angeles, said that the numbers conform to what he has seen in his research. The gun buyback could definitely have contributed to the decline in intentional homicides in the city. And domestic violence rates could have seen a rise as a result of the pandemic lockdown measures and related stresses, a trend he said has also been observed in the United States during the pandemic.

Furthermore, such long-term societal changes take time to be seen in the stats. “There’s going to be a lag. It’s not going to have an immediate effect,” said Blum, who added that it could take five to ten years to see results of the toy exchange program, as socialization processes generally take longer to be developed and observed.

Still, parents who attended the event with their children were excited to see an immediate effect of the program in their homes. Giovani González brought his two daughters and four of his nephews to the event. He was looking forward to getting in on the fun himself and what that will mean for his family.

“It helps the kids connect with us better,” he said. “As parents, we’re not too into playing with toy guns. They like to play like they kill each other, cops and robbers, you know. But my daughters got some puzzles, and now we’ll be able to do that together and interact better with them and build stronger family ties.”